The Black Hand Boys

By Neil O’Dwyer

Every Wednesday I’d arrive home from school to a stack of newspapers outside my front door and a five-pound note in an envelope in my letterbox.

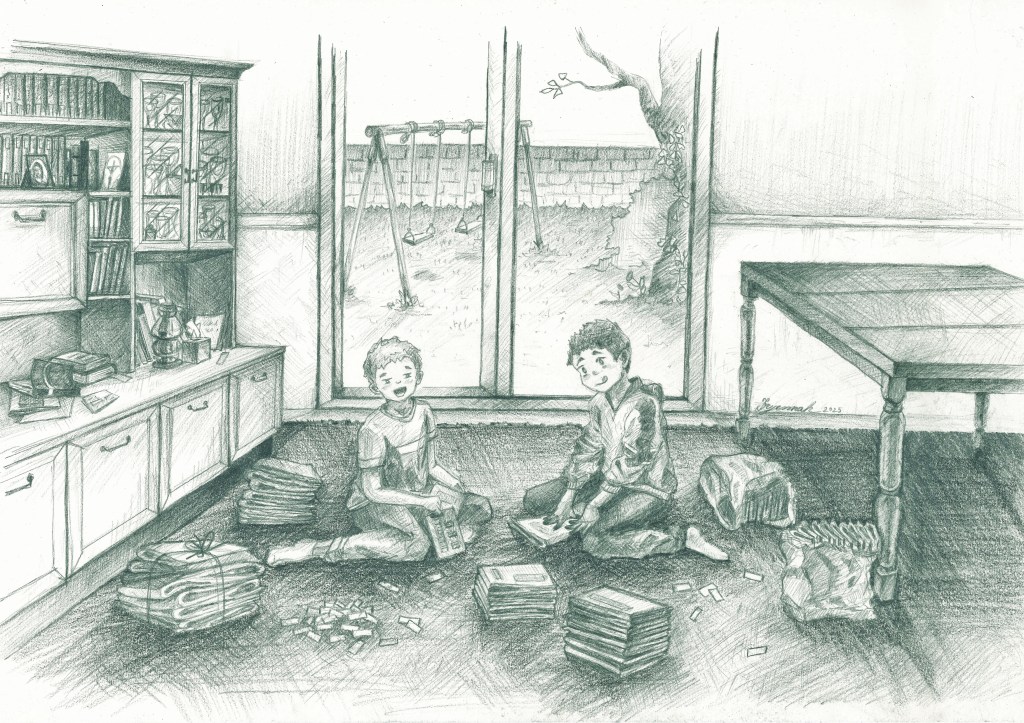

Peter stayed at my house for a few hours after school, so it made sense for us to do the paper round together. We folded and bagged the papers enthusiastically on my dining room floor until our hands were black and our attention waned. Then my mother took over.

This was the best idea we’d had since inventing our own language.

There were 165 houses to cover across five streets (including our own), and one of them had forty-six semi-d’s and went on forever. In the early days, we walked every step of the route together and basked in our shared entrepreneurial spirit. Summer was coming and the days were stretched.

The promise of payday carried us effortlessly over the streets, but after the initial excitement passed it seemed to take us longer and longer to get the route finished. Sometimes we had leaflets or shower gel packets and this slowed down operations. All for one extra pound a week!

Our friend Sully was also in the industry but he delivered his papers on rollerblades and made it look easy while we trudged around on foot with bloated plastic bags bashing against our bare calves.

Eventually, we started to split the route to save time, and Paco, the local anarchist, would sometimes join Peter on his section. I used to regularly get in scraps with my brother and Peter fought with Sully, but we all fought with Paco. Soon enough the little shit was whispering in ears and now Peter wanted to open the envelope.

Let him open it, Paco said. You always get to open it.

I look back and wonder if money was at the root of my lifelong friendship with Peter finally starting to drift, but from then on he opened the damn envelope every second week and sometimes he kept the fiver and gave me coins. Unfortunately, though, these perks didn’t have the desired effect on his performance.

One rainy day in June we arrived back home to see we’d forgotten to fold the shower gel samples in with the papers, but Peter was already on the swings in the garden and wouldn’t budge. I had the foamiest showers of my life that week. On the following Wednesday we found our cash wrapped in a note from the boss stating that she knew the samples hadn’t been delivered.

She had someone on the inside.

The following week Peter hiked the long street with Paco and said they had eight extra papers left over and shoved them all in one letterbox and walked to the shops. I always hated delivering to that address from then on. But Peter was only ever in it for the money, and since his family had plenty of it, I knew he wasn’t going to be a lifer.

So, he walked away and my workload doubled. But I was happy with the extra cash and the responsibility of running the business on my terms. Sully quit his route too after discovering a new source of income – he drafted himself up a little sponsorship card for a charity rollerblading race and rolled from door to door, collecting over £27 in one day.

Meanwhile things were slow going back at the dining room. My mother carried the brunt of the extra folding while Peter was on leave, happily passing the time on my swing in the sun.

An unwelcome feeling started creeping up inside me and I started to analyse the costs involved in giving my mother a commission while stubbornly carrying two full bags of newspapers with me, even though my route went back towards my house at various points. I started to tire. The effort of trudging up and down 165 driveways was getting too much, so I started scaling walls and pushing through bushes to avoid any extra steps. I left my bags down against a wall and circled the crescent without the dead weight but emerged from an overgrown garden horrified to see a bag had toppled over and some papers had spilled out and unfolded. I ran across the road cursing the South Dublin News Company and was in a foul mood the whole way around the block and all through dinner until I heard the sound of the ice-cream van.

Paco was in the queue and in my ear.

Just dump them, he said.

In plain sight, I walked to the end of my road, hopped the wall into the field and flung one long street’s worth of papers into a ditch. Talk about shitting on your own doorstep. There was only one person around here delivering papers now and everyone knew who that was. I had black blood on my hands and went home and prayed for torrential rain.

I experienced some occasional dread during the ad breaks of my cartoons, but sure enough on the following Wednesday my money arrived along with a fresh stack of papers and some new unwanted emotions.

I learned that crime does pay, but the guilt will kill you.

The only thing worse was having to deliver 165 more newspapers that week and every week forever after, so I quit, dug my rollerblades out of the wardrobe, and went out to play.

A date for the charity rollerblading race has yet to be finalised.

Neil O’Dwyer

Neil O’Dwyer is a teacher from Dublin. Outside of teaching he regularly participates in story telling events in the city.

Photo credit: Fabien Barral